Belief and Believeability Volume 16 ANTHROPOLOGY | NEWSLETTER JUNE 2023

Table of Contents

Letter from the Chair 2-4

Reflections 5-25

Tanya Lurhmann “Why Do We Believe What Seems Irrational, At Least to Others?”

Serkan Yolaçan “The Specter of ChatGPT: Thoughts on Genre, Entertainment, and Truth”

Alev Cinar “Can Islam Theorize Politics?”

Saad Lakhani “Saint or Blasphemer: On Getting Friendly with God”

Alisha Cherian “Stories and Everyday Archives of Truth”

Barbora Spalová “Beliefs and Believability During the Fieldwork in Mayfair and Washington - Guadalupe”

Miray Cikaroglu “Studying the Post-Imperial in Post-Disaster Turkey”

Interviews 20-26

Jean-Thomas Martelli

Tatjana Thelen

Denise Gill

Faculty News 27-28

Department News & Events 29-30

Staff News 31-32

Letters from the Field 33-40

Noor Amr

Emilia Groupp

Shikha Nehra

Stefania Manfio

Paras Arora

Undergrad Fieldnotes 41-42

Ilina Rughoobur

Alumni Updates 43-50

Achievements 52

Student

Hector M. Callejas Anthropology

Faculty 53-54

Alumni Spotlight: Kim Grose Moore

LETTER FROM THE CHAIR

By Thomas Blom Hansen

A new vocabulary entered public debates in much of the world less than a decade ago: alternative facts, fake news, hyper partisanship, deep fakes, media echo chambers, chatbot campaigns, trolling and much more. Much of this has been attributed to the global spread of social media platforms, the rise of rightwing populism and the proliferation of conspiracy theories across the world. There is little doubt that systematic deployment of troll armies and disinformation campaigns have become standard weapons of choice by political partisans as well as by many governments. We saw this in the fog of disinformation around the pandemic, and we see how dis- and misinformation are crucial weapons in the war in Ukraine.

However, what seems like a rapid shift in how belief, credibility and truthfulness are claimed is, in fact, premised on longstanding and gradual transformation of how truth claims and authoritative knowledge have been produced and projected in public life in recent decades.

The authority of expert knowledge and of academic procedures of knowledge production are more contested today than ever before. While earlier debates in anthropology in the 1980s and 90s revolved around the potential of academic knowledge being extractive and being harmful to informants from vulnerable communities, the situation is rather different in the current age of social media, hyper-connectivity and ubiquitous global use of cell phones, cameras and other devices. Today, individuals and communities across the world engage in documenting, projecting, filming and uploading massive amounts of digital materials. Most of it is private and meant for entertainment, other parts seek to represent and project various historical, political and spiritual claims. Much of the latter kind of material appear on websites or videos, often framed as reporting, or presented as ‘para academic’ knowledge that adheres to some academic procedures

of argument and referencing, for example. The latest element in this shift is the debate about AI enhanced knowledge production and the now notorious device known as ChatGPT- capable of faking most student essays, we are told. The net result is a cacophony, multiple spheres of reality, and multiple layers of claims and counter claims that often appear as an ever-expanding hall of mirrors. In other words, an environment ripe for misinformation campaigns, ‘factoids’ of dubious origins, troll armies seeking to sway public opinion and influence elections. No wonder that so many feel exhausted and disoriented, including fact checkers and social scientists whose jobs are to separate fact from fiction.

This emerging reality presents at least two challenges to anthropology as a discipline. First, anthropology as a discipline has to embrace the fact that the knowledge and interventions we produce cannot necessarily claim any self-evident authority as ‘expert knowledge’. Rather, we are all part of an ongoing, and often polarized conversation with communities and interlocutors wherever we work. Contemporary anthropologists have to establish their relevance and value by the quality and depth of their work amidst a flurry of competing truth claims and strong emotional claims to identity, history and cultural values. This is easier said than done, especially in the social sciences where the realities we study are reflexive and dynamic and where those we study are likely to take issue with what we write about them and their societies and communities. Today, many anthropologists face intense criticism, trolling and at times outright threats from political partisans, as well as stonewalling and visa denials by hostile governments. However, we should not be deterred or scared by this new reality but rather embrace the fact that scholarly work by anthropologists and many others is more accessible and more widely circulated than ever before. It does not just dwell in rarefied circles and ivory towers but has an impact in the world. That means

that there is nowhere to hide and that every anthropologist must be accountable for what they write and the claims and arguments they make. It also means that we cannot always predict, let alone control, how our writing and statements are used, cited and deployed by friends, or foes. So, unlike a previous era where the academic profession and its disciplines were accorded a measure of public respect and credibility, each of us now has to earn and maintain our own credibility by presenting distinct and believable arguments in the scholarly community, and in the public spheres we are part of.

The second challenge is that the way beliefs are held, and the ways believability, credibility and truth claims are established among diverse communities appear more complex than ever. Anthropologists of religion have long demonstrated that active faith in divine forces, or the possible existence of a god, are only some of the factors that shape religious activity and identity. In many parts of the world, religion is less a question of individual belief than the community you are born into. One can lose faith, or never really believe, but one can still be strongly attached to an ethno-religious category, for example. The question of belief and believability are rarely just based on private convictions or deliberations. What to believe, and what seems believable and credible to individuals and communities, are entangled with larger ethical concerns, strident public debates and often stubborn narrative frames and stereotypes that are more often than not impervious to academic or legal standards of proof and falsification. But again, there is nothing new about this. The current worries about perils posed by the circulation of outlandish conspiracy theories on social media notwithstanding, wild speculation, rumors and elaborate webs of falsehoods and misinformation are features of most societies, and much of human history. They are also close cousins of gossip, another universal and often highly entertaining human activity that also often provide the ethnographer with important clues as to what is considered scandalous, contentious and risky in a community or social network. What strikes many as disconcerting is perhaps that conspiratorial frames, images and rumors are no longer shared and furtively enjoyed, and believed, in smaller circuits or fringe corners of society. They are now in the mainstream of news and public speech. But even that is not new. As Richard Hofstadter showed in his remarkable 1964 book The Paranoid Style in American Politics, conspiracy thinking and fears of ‘plots against America’ are as old as the republic itself. Paranoia, Hofstadter argues, is a remarkably stable substrata of American public and private life, fueled by fears of emancipated Black communities, by ‘culturally alien’ migrants in the

early 20th century, and now again in the 21st, by fears of communism, or fears of gender fluidity, diversity programs and flexible pronouns that now are portrayed as the latest threat to western civilization. Similarly ‘paranoid styles’ can be found in many other parts of the world where racial and ethnic stereotypes and prejudices based on class and caste have proven remarkably stable and hard to properly address and overcome. Such stereotypes, rumors and prejudice have changed very little for generations, they seem to re-emerge in each generation, each time draped and articulated a little differently but still revolving around racial and social fears, apprehensions, and fragilities that both divide and knit together communities with remarkable, and often disturbing, historical continuity. This persistence of certain kinds of beliefs and ‘truth’ about the other, however outrageous and insidious these may be, is a driving force that structures the behavior and preferences of billions of people. It also shapes political life in most of the world. Yet, it is a problem that neither anthropology nor other disciplines have been able to explain, and account for in any conclusive manner. But we keep trying, as we should, and few try harder and with more eye for detail and historical specificity than anthropologists, I am proud to say.

For this year’s newsletter, we invited faculty and students to reflect on the questions of belief, truth claims, believability and the status of the knowledge we produce. We invited reflections based on ongoing scholarly work; based on experiences as field workers; or based on general intellectual observations.

We begin with a number of contributions that directly tackle the theme of belief and believability. Tanya Luhrmann discusses her research over many years with people and communities who are strong believers in divine and more-than-human forces. Luhrmann draws on the term ‘paracosm’ to describe the worlds and imaginations that people create for themselves, and share with others, within which they can secure truths and certitudes that give deep meaning to their life. Serkan Yolaçan reflects on the much-discussed phenomenon of ChatGPT as a form of entertainment, as an ironic play with the very boundaries of a genre of seemingly earnest output from an AI device that after all does know how to have fun, or to pun – as yet. Saad Lakhani shares an anecdote about an unusual Sufi pir (spiritual guide/master) in Pakistan who cracks jokes about otherwise sensitive topics and yet seems to be protected by his reputation for deep faith and learning. Our academic visitor, Alev Cinar of Bilkent University in Ankara, speculates how Islamic concepts and ethics are translated into a contemporary vocabulary of political

3

life in Turkey. Drawing on her fieldwork in Singapore, Alisha Cherian demonstrates how ethnic stereotypes turn into more sedimented beliefs about other groups. Miray Cikaroglu reflects on how dramatic events and disasters, such as the recent devastating earthquake in southeastern Turkey, affects political discourse and the believability of political leaders, and the outcomes of elections. Another of our academic visitors, Barbora Spalova, contemplates the appeal of belief and healing among individuals attending churches and Bible study groups in mainly Latino neighborhoods in San Jose.

We then turn to interviews with two academic visitors, Tatjana Thelen, Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Vienna who has taught several classes in the department; and Jean-Thomas Martelli, a political sociologist and Fellow at the International Institute of Asian Studies in Leiden, who is visiting in the spring and summer.

We then turn to interviews with Hector Callejas, who is part of the university wide IDEAL program on campus; and Denise Gill, ethnomusicologist focusing on Turkey, and Associate Professor in the Department of Music on campus.

In keeping with longstanding tradition, we carry letters from graduate students in the field – Noor Amr (Germany), Paras Arora (New Delhi, India), Emilia Groupp (Tunisia), Stefania Manfio (Mauritius) and Shikha Nehra (Assam, India), as well as one of our undergraduates, Ilina Rughoobur (Mauritius).

The remainder of the newsletter is devoted to our usual rubrics:

(1) Updates from the faculty, including a celebration of Sylvia Yanagisako who is retiring this year after more than four decades in the department.

(2) Staff updates, including appreciations of Ellen Christensen who retired in September 2022 after many years as Department Manager, and Shelly Coughlan who left the department for new challenges after many years as graduate Student Service Officer. We welcome new faces: Emily Bishop, our new and dynamic Director of Finance and Operations (Department Manager); John Lee, our new Assistant Director of Finance and Operations, and Julianne Spitler, our new Administrative Assistant.

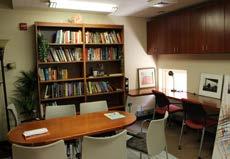

(3) We celebrate our return to normal in-person activity with photos from our many department events and new spaces for students.

(4) Last but not least, we bring updates from our many alumni, including an interview with Kim Grose Moore who also kindly addressed our undergraduates at the Alumni Career Night.

I want to extend a warm note of thanks to our faculty, students, visitors and staff for a wonderful and active academic year. It is so great to be back!

4

Why Do We Believe What Seems Irrational, At Least to Others?

I am an anthropologist of religion. I did my first stint of fieldwork with middle-class Londoners who identified as witches, druids, and initiates of the Western Mysteries. My next project was in Mumbai, India, where Zoroastrianism was experiencing a resurgence. Later, I spent four years with charismatic evangelical Christians in Chicago and San Francisco, observing how they developed an “intimate relationship” with an invisible God. Along the way, I studied newly Orthodox Jews, social-justice Catholics, AngloCuban Santería devotees, and, briefly, a group in Southern California that worshipped a US-born guru named Kalindi.

By Tanya Luhrmann

Professor of Anthropology

March 1997, the bodies of thirty-nine people were discovered in a mansion outside San Diego. They were found lying in bunk beds, wearing identical black shirts and sweatpants. Their faces were covered with squares of purple cloth, and each of their pockets held exactly five dollars and seventy-five cents.

The police determined that the deceased were members of Heaven’s Gate, a local cult, and that they had intentionally overdosed on barbiturates. Marshall Applewhite, the group’s leader, had believed that there was a UFO trailing in the wake of Comet Hale-Bopp, which was visible in the sky over California that year. He and his followers took the pills, mixing them with applesauce and washing them down with vodka, in order to beam up to the spacecraft and enter the “evolutionary level above human.”

In the aftermath of the mass suicide, one question was asked again and again: How could so many people have believed something so obviously wrong?

Most of these people would describe themselves as believers. Many of the evangelicals would say that they believe in God without doubt. But even the most devout do not behave as if God’s reality is the same as the obdurate thereness of rocks and trees. They will tell you that God is capable of anything, aware of everything, and always on their side. But no one prays that God will write their term paper or replace a leaky pipe.

Instead, what their actions suggest is that maintaining a sense of God’s realness is hard. Evangelicals talk constantly about what bad Christians they are. They say that they go to church and resolve to be Christlike and then yell at their kids on the way home. The Bible may assert vigorously the reality of a mighty God, but psalm after psalm laments his absence. “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” Beliefs are not passively held; they are actively constructed. Even when people believe in God, he must be made real for them again and again. They must be convinced that there is an invisible other who cares for them and whose actions affect their lives.

This is more likely to happen for someone who can vividly imagine that invisible other. In the late 1970s, Robert Silvey, an audience researcher at the BBC, started using the word “paracosm” to describe the private worlds that children create, like the North Pacific island of Gondal that Emily and Anne Brontë dreamed up when they were girls. But paracosms are not unique to children. Besotted J.R.R. Tolkien fans, for example, have a similar relationship with Middle-earth. What defines a paracosm is its specificity of detail: it is the smell of the rabbit cooked in the shadow of

5

REFLECTIONS

the dark tower or the unease the hobbits feel on the high platforms at Lothlórien. In returning again and again to the books, a reader creates a history with this enchanted world that can become as layered as her memory of middle school. God becomes more real for people who turn their faith into a paracosm. The institution provides the stories — the wounds of Christ on the cross, the serpent in the Garden of Eden — and some followers begin to live within them. These narratives can grip the imagination so fiercely that the world just seems less good without them.

During my fieldwork, I saw that people could train themselves to feel God’s presence. They anchored God to their minds and bodies so that everyday experiences became evidence of his realness. They got goose bumps in the presence of the Holy Spirit, or sensed Demeter when a chill ran up their spine. When an idea popped into their minds, it was God speaking, not a stray thought of their own. Some people told me that they came to recognize God’s voice the way they recognized their mother’s voice on the phone. As God became more responsive, the biblical narratives seemed less like fairy tales and more like stories they’d heard from a friend, or even memories of their own.

Faith is the process of creating an inner world and making it real through constant effort. But most believers are able to hold the faith world — the world as it should be — in tension with the world as it is. When the engine fails, Christians might pray to God for a miracle, but most also call a mechanic.

Being socially isolated can compromise one’s ability to distinguish his or her paracosm from the everyday world. Members of Heaven’s Gate never left their houses alone. They wore uniforms and rejected signs of individuality. Some of them even underwent castration in order to avoid romantic attachments. When group members cannot interact with outsiders, they are less likely to think independently. Especially if there is an autocratic leader, there is less opportunity for dissent, and the group becomes dependent on his or her moral authority. Slowly, a view of the world that seems askew to others can settle into place.

When we argue about politics, we may think we are arguing over facts and propositions. But in many ways we argue because we live in different paracosmic worlds, facilitated these days by the intensely detailed imaginings of talk radio and cable news. For some of us, that world is the desperate future of the near at hand. If abortion is made illegal, abortions will happen anyway, and women will die because they used clothes hangers to scrape out their insides. Others live in a paracosm of a distant future of the world as it should be, where affirmative action is unnecessary because people who work hard can succeed regardless of where they started.

Recently, the dominant political narratives in America have moved so far apart that each is unreadable to the other side. But we know that the first step in loosening the grip of an extreme culture is developing a relationship with someone who interprets the world differently. In 2012, for example, a woman named Megan Phelps-Roper left the Westboro Baptist Church, a hard-line Christian group that pickets the funerals of queer people, after she became friendly with a few of her critics on Twitter. If the presence of people with whom we disagree helps us to maintain common sense, then perhaps the first step to easing the polarization that grips this country is to seek those people out. That’s the anthropological way.

6

REFLECTIONS

Image from When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God

The Specter of ChatGPT: Thoughts on Genre, Entertainment, and Truth

The pandemic made such adjustments visible as we had to shift between different platforms and genres of learning. Virtual platforms like Zoom and YouTube were tested as potential alternatives to traditional classroom settings and social events on university campuses. Regardless of how we felt about it, we honed our communication skills through new features that allowed us to raise hands, share screens, or have a little chat on the side. The pressure to be discreet was recalibrated. One must be subtle when checking their phone to avoid drawing attention in a seminar. However, watching a debate on YouTube does not require the same level of decorum from its audience, not even the semblance of attention. On Zoom, one’s presence can be reduced to sound, image, or words. Forgetting to unmute became a common mistake, drawing sympathetic smiles from others. Turn the camera off, and poof, you are gone! Are you there? Maybe. Maybe not.

By Serkan Yolaçan

Professor of Anthropology

A new specter is haunting universities and the genres of learning they privilege—the specter of ChatGPT. As we are using this magical tool, testing its limits, and developing sensibilities about its appropriate uses, we are turning it into a new genre of learning. But what do we mean by learning? And what do we mean by genre? And what do they have to do with the theme of this newsletter, “belief and believability?” We have a lot to unpack before returning to ChatGPT at the end.

First, what do we mean by learning? Acquiring knowledge? Discovering a new perspective? Having a new experience? Being inculcated moral values? However we define it, learning adjusts us to our environment in new ways, and learning involves learning how to inhabit this new condition. The truth of what we learn emerges from our understanding and participation in this adjustment, no matter how minuscule and ordinary or grand and “life-changing” that adjustment may be.

The pandemic may have highlighted how our learning experiences involve developing a sense of the rules of engagement, social expectations, and proper conduct that enable and limit it. But this dynamic pervades our lives through other genres that do not need the high-functioning infrastructure of the University or the Internet. Take something as trivial as gossip:

“Gossip is a text crafted with many signals of confidenceandconspiracy,highlightedwithaglance to see if somebody is listening, phrased to titillate with the most savoury or unsavoury bit reserved for the ending. One could not divorce the inflections of voice, the body posture, the signs of intimacy from all the techniques of story-telling in a gossip’s performance of history. We who hear the gossip have a fine sense of its poetics as we separate the snide from the good-humoured, commit ourselves or suspend our judgement of its truth, know which friendly relations are damaged or enhanced by it,” (Dening 1995, 14).

Despite practicing it from early on in our lives, we hardly pay attention to gossip as a genre of communication and learning. Part of the reason is that gossip is a self-effacing genre, much like a joke. Both genres deflect any serious

7

REFLECTIONS

reflection on them and dissolve when exposed to scrutiny. Ah, it’s just gossip, we say. Or, come on, it was a joke, we exclaim to remind the other party about the genre and how it is supposed to be inconsequential. These unassuming genres lower the stakes of learning, and that is precisely why we keep turning to them to communicate ideas, mores, disagreements, and paradoxes. And the more we use them, the more they become second nature. These low-stake genres are most effective in lighthearted moments that taper, overrule, or even ridicule the seriousness of other genres, that is, in moments when we feel at ease or, even better, entertained.

Entertainment may sound frivolous at first. But as I have already suggested, we should not be too quick to associate learning with sobriety. Not yet. Not before we acknowledge the God of Entertainment who rules us all through our smart gadgets, digital platforms, and the endless content that fills them. Some may prefer to dismiss our obsession with entertainment as the fetish of our age, a monster of our own creation that needs to be overcome. I approach it differently and ask what aspect of the human condition is exaggerated in this obsession. Could it be our proclivity to play?

The modern distinction between work and leisure has obscured what Victor Turner calls “the human seriousness of play” (2001 [1982]), a characteristic of “all symbolic genres from ritual to games and literature” (1974, 66). Our engagement with the world through these genres can be earnest and playful at once. And in play, we learn. This recognition drops us in the Dionysian domain of pleasure, festivity, ritual, theater, dramaturgy, and performance. Anthropologists have been charting this domain, generating perspectives on the human experience as performance bound in symbolic exchanges. On that firmer ground, Greg Dening helps us expand the notion of entertainment:

“Entertainment comes ultimately from the latin inter tenere ‘to hold among or between.’ Of the sixteen dictionary usages of the word ‘entertain’ onlyoneusageisdevotedtothefrivolousoramusing element in it. All the other usages stress its active, defining quality: ‘to keep in a certain state,’ 'to support,’ 'to engage,’ keep occupied the attention of,’ 'to harbour,’ 'to take upon oneself.’ Entertaining a thought or entertaining a guest has a boundarymaking, dramaturgical character. If I entertain a guestIputallsortsofboundarymarkersaroundour host/guest relationship. I do things with extravagant gesture, out of the ordinary. I place my guest at table, I dress carefully, I formalize the menu, I use special utensils, I move the conversation away from sensitive issues. I play the role of host in a thousand small ways and the guest responds as dramatically. Our host/guest relationship is presented in dramatic actions," (1995, 75-76).

Entertainment requires a deep familiarity with a genre and inhabiting it earnestly. In that focused engagement, the boundary between work and leisure starts to break down. In an entertained state of mind enabled by specific genres, we observe and participate in dramatic compositions, navigate their boundaries, discover their twists and turns, and resolve their tensions.

Understanding the problem of truth first and foremost as a problem of genre allows us to approach the theme of this newsletter, “belief and believability,” beyond the binaries of fact vs. fake or faith vs. reason. The truth of a news article is different from the truth of a poem or both from the truth of a historical novel. We may expect a factual basis from a news article, but demanding such evidentiality from a poem would only reveal our ignorance of the genre. With the historical novel, the same expectation would possibly generate an interesting discussion on the genre’s limits.

What should we expect from ChatGPT as a genre of learning? What questions should we ask of it? How do we understand the truth of what we learn from or through it? For many, ChatGPT is as frightening as it is entertaining. But what are we afraid of exactly? Losing the authenticity of an authorial voice pegged to a single living being that has a physical and social presence? Loss of the modern subject? Even the idea of self? What if I told you that ChatGPT wrote this piece? Would you feel differently? Would you believe me? Who exactly is me?

As all that is solid melts into a hivemind, we are yet to see what human proclivities will be dramatized by this genre. Will it be our unquenchable appetite to decipher the human condition? Will ChatGPT, the ultimate linguistic hivemind, finally divulge the answers for us? Will those answers entertain us? Or will we be entertained by the irony of it all and have a good laugh about it, like it’s all a joke?

References

Dening, Greg. The death of William Gooch: A history’s anthropology Melbourne University Publish, (1995).

Turner, Victor. “Liminal to liminoid, in play, flow, and ritual: An essay in comparative symbology.” Rice Institute Pamphlet-Rice University Studies 60.3 (1974).

Turner, Victor. “From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play (1982).” Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP (2001).

8

REFLECTIONS

Can Islam Theorize Politics?

By Alev Cinar Visiting Scholar

By Alev Cinar Visiting Scholar

I’m at the Anthropology Department as a Visiting Scholar with an EU Horizon2020 Marie S. Curie Global Fellowship, working on a project titled “The Islamic Intellectual Field and Political Theorizing in Turkey.” My core objective is to understand the relationship between Islam and politics through an investigation of Islambased intellectual and political movements that are currently active in the intellectual field in Turkey, which has not only shaped the foundational ideology of the ruling Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP), but has also been instrumental in the transformation of the overall language, culture, and practice of politics during the last two decades, from the political system, including the structure of government, foreign affairs and economic policies, to the conceptualization of national history, the education system, and various cultural policies including culinary practices, “ethnic sports” or the fashion industry. Despite its significance, however, this intellectual field and the movements that constitute it have not been

studied academically, neither internationally nor by the Turkish academia. I speculate that there are at least two reasons for this neglect. First, since academic disciplines are still largely dominated by a paradigm that is rooted in the religion vs. science binary, there is a strong tendency to look at everything related to Islam as belonging to the domain of religion and faith, rather than political thought, which is an attitude that breeds a strong reluctance to see Islam as a legitimate domain of knowledge production that is capable of generating politically, economically, or socially viable perspectives and systems of thought. Second, the “Islam vs. West” binary, which has been cultivated as an antagonistic opposition both by extremist, radical or authoritarian Islamic movements, including the AKP, and by right-wing populist-nationalist movements in the global North, also taints academic discourses. This binary thinking has not only fueled formidable prejudice against Islam in general, but also fosters reductionist and essentialist approaches in the academia, which tend to

Variations of Sufism in Turkey

Orthodox/Naqshbandi

Unorthodox

9

Alev Çınar 2023

The Predicament of Islamic Decoloniality in Turkey

Sufism (e.g., İskenderpaşa, İsmailağa, Erenköy, Menzil)

“The Imam Rocker” Ahmet Muhsin Tüzer, who combines Sufi music with Rock

The Naqshbandi Menzil Tariqa, which has close ties with the AKP and several ministries.

Sufism: (e.g., Malāmatiyya, Qalandariyya, Bektashi)

The Predicament of Islamic Decoloniality in Turkey

REFLECTIONS

REFLECTIONS

frame Islam as a monolithic category that is essentially and irredeemably separate from the West. Under these intellectually adverse conditions, the study of Islam-based intellectual and political movements is often frowned upon by many in the academic world – both internationally and in Turkey – who tend to see such studies as running the risk of legitimizing radical and extremist forms of political Islam, or inevitably serving the interests of populist or authoritarian regimes like the AKP. In my work, I attempt to critically address and complicate, hopefully without reproducing, the religion-science, faith-knowledge, or the Islam-West binaries to break away from the binary logic that has tainted, and so far undermined, the study of the relationship between Islam and politics.

What inspired me to introduce my work to the Stanford Anthropology community in this way was the following statement of this year’s newsletter theme:

One can lose faith, or never really believe, but one can still be strongly attached to an ethno-religious category, for example. The question of belief and believability are rarely just based on private convictions or deliberations.

I find approaching religion as a category of identification and belonging rather than faith a refreshing intervention that helps break away from the forms of binary thinking that I tried to outline, which is one of the central objectives of my study. But even more central is making this intervention by introducing the significance of religion as a category of political thought, that is, as a source of theorizing the political and the social. In other words, I’m interested in demonstrating how truth, or rather, theoretical and normative insights are sought in intellectual traditions rooted in religion, which is itself a domain that is historically and intellectually inseparable from science and philosophy. More specifically, I am interested in understanding how,

in the Islamic intellectual field in Turkey Islam provides the intellectual tools with which existing socio-political systems and their foundational ideologies are contested or re-envisioned, and how new perspectives and systems are developed to replace them. In my approach to the study of Islam-based political theorizing as a sort of knowledge production, I am not concerned with the truth value of the claims made but rather with their functionality. In other words, I seek to discern how Islam-based postulates, perspectives and ways of knowing are used to justify political projects, foundational ideologies, or policies, and to serve as tools of political legitimation, justice, accountability, or social welfare and wellbeing by different movements in the Islamic intellectual field in Turkey.

Conducting this research under the sponsorship of Thomas Blom Hansen and the Anthropology Department at Stanford, and the network of scholars I met in the Abbasi Program in Islamic Studies, as well as the Program on Turkey at the Freeman Spogli Institute has been immensely valuable and conducive to the interdisciplinary approach and the unconventional themes I am pursuing. Being a scholar based in political science who is interested in the intellectual foundations of politics and the theorization of the political by the locally established intellectuals themselves, and as someone who wants to maintain a critical distance while also deeply engage their intellectual culture, I found the criticism and feedback coming from anthropological perspectives, and the diverse audiences I was able to interact with at Stanford, most conducive to the kind of work I am doing on the Islamic intellectual field in Turkey. After the end of my fellowship in August 2024, my plans are to seek residential fellowships where I hope to bring together this work in a book. I would love to take advantage of the immensely favorable intellectual environment I found at Stanford by coming back through a possible Stanford Humanities Center fellowship.

Continuation on Page 7

10

Alev Çınar 2023

the Islamic Intellectual Field: ongoing political theorizing in hundreds of journals and magazines

The Predicament of Islamic Decoloniality in Turkey

Saint or Blasphemer: On Getting Friendly with God

By Saad Lakhani

Doctoral Candidate

Rizwan spotted us on his motorcycle and walked back with us to Deen Muhammad’s drawingroom/TLP’s makeshift office. We had just returned from door-to-door political campaigning for the Tehrik Labaik Pakistan (TLP), a popular anti-blasphemy movement, in Lahore’s working-class Walton Road neighborhood. Deen Muhammad yelled out as we stepped in, “six cups of chai!” I had dinner with Deen Muhammad earlier, so he turned to Rizwan to ask if he would like something to eat. Excusing himself, Rizwan half-jokingly said that he better leave soon, or he’ll get “a beating from his wife.” Rizwan had promised his pregnant wife to rush home from work but was with us instead.

Upon hearing Rizwan’s comments, Deen Muhammad remembered a story about the Pir of Kot Abdul Malik, a small town outside Lahore. Deen Muhammad was a retired carpenter whose favorite pastime was to tell miraculous stories about Sufi Pirs.

“You know that I am a disciple of the Pir of Walton [Road],” Deen Muhammad said to Rizwan, “this funny story is about a different Pir.” He continued, “so, a good friend once asked me to join him for Friday prayers at Kot Abdul Malik. He was a disciple of the Baba Ji [literally: father dearest] over there. I quickly fell in love with Baba Ji and visited every Friday for fifteen years. That is, until Baba Ji took a veil from this world.”

Expressing his love for the Pir, he further said, “Baba Ji! What can I say about him? A tall six-and-a-halffoot Qadiri! A beautiful man with a glowing (noorani) face. He was a true friend of God, a dervish-type man. To be honest, I even felt like skipping prayers to keep looking at him and listening to him speak all day long.”

He then remembered after a sigh, “Oh yes, I was telling you a story.”

During his first meeting, Deen Muhammad had conventionally asked the Pir to teach him some spiritual lessons. “You know what he said? This is how you can tell that he was authentic. Baba Ji told me, ‘When you ask your neighbor’s kid to fetch your undergarments, you should expect a beating from your wife.’”

Rizwan and Deen Muhammad burst out laughing. While a playful response to Rizwan’s earlier comments, the story had a moral to it. Since Deen Muhammad had already pledged discipleship to another Pir, the Pir of

Kot Abdul Malik was effectively telling him that his primary source of moral and spiritual sustenance should be his own Pir.

In Pakistani Punjab, the Pir-disciple relationship is often understood through the analogy of the marriage contract. Just as a good wife must be loyal to her husband, a loyal disciple must be wary of the enticements and entrapments of other Pirs.

For Deen Muhammad, the fact that the Pir did not actively try to seduce him was a sign of the Pir’s authenticity as a ‘friend of God,’ the Islamic term for sainthood. “This is also a sign of a true Friend [of God]. Any other Pir would say, ‘oh your Pir, he’s nothing. I am the true big shot, real deal Pir. Your Pir hasn’t taught you anything valuable. Let me tell you the real stuff!’”

Having already kickstarted his favorite topic, Deen Muhammad continued to tell us many Pir stories. “Another funny one,” he said. “So Baba Ji always arranged a langar [communal feast] after the prayers. There’d be sweet rice, Halwa, and the like.” Deen Muhammad chuckled before adding, “So, this one time, he overheard a boy tell his friend to avoid getting food stains on his white clothes. The Pir Saheb [mockingly] said, “oh, don’t worry. I’ll even clean your face if I have to with my own hands.”

The joke was that the boy was being effeminate and overly sensitive.

Deen Muhammad told another story, “This one time, a young newlywed man met Baba Ji and asked him to pray for a child. When the Pir learned that the man had just gotten married, he told the man ‘Do you just

11

A local TLP rally in Lahore against “global blasphemers”

REFLECTIONS

want me to pray or should I do the deed for you too.’”

After sharing a generous laugh with Rizwan, Deen Muhammad told a story about a wealthy old man “around eighty to ninety years of age” requesting to become a disciple. The Pir told him, “Where were you your whole life? Don’t you think you’re a little late? Look, all your nut bolts have become loose?” After pulling his leg some more, the Pir eventually accepted his discipleship offer, saying “okay, okay, we will work with what we got.”

After a brief pause, Rizwan bowed his head and remarked, “Ah, Baba Ji combined sincere love with jokes.” Deen Muhammad added, “his jokes came from sincere love.” He then turned to me, “You see, Saad bhai, Baba Ji had a funny temperament... it was his unique way to do ethical training.” Whether or not the Pir’s jokes had a deeper ethical meaning, they did reproduce an asymmetrical joking relationship of the Pir with his followers: the Pir could mock, tease, and even insult social others, but they could not return the favor. In fact, failing to live up to the norms of deference and avoidance toward a Sufi Pir may even result in an accusation of blasphemy.

Often, joking relationships establish parity in which both parties exchange banter and insult. These exchanges allow individuals to suspend social formality and allow for a more boundary-free, intimate bond to emerge. In this light, the Pir’s joking insults were interpreted by Deen Muhammad as expressions of intimacy and informality that disregarded ordinary social distances about respecting the dignity of others in day-to-day life. This becomes apparent in the Pir’s consistent disregard of bodily boundaries; in saying he’ll wipe a boy’s face with his hands or joking about sex with another man’s wife, or by mocking an old man’s body. The fact that the Pir could get away with it was a demonstration of power and authority. Especially given the fact

the Pir’s active disregard of formal respect toward others goes hand in hand with the taboo regulating deference and avoidance demands for the Pir himself.

Deen Muhammad’s next stories took a more miraculous turn. This one time, he said, the Pir was visiting the city of Jhelum where there was a tea shop that he loved to frequent. He asked for his favorite tea-maker Fazal (literally: "grace") but learned that Fazal had just passed away. “Such divine grace [fazal] it was,” the locals said, that the Pir arrived since he could lead the funeral prayer at the town center.

Deen Muhammad’s next miracle story, he said, was even more shocking because he witnessed it first-hand. This one time he arrived at Kot Abdul Malik during a rainstorm, and it seemed impossible to pray under such conditions. That’s when the Pir angrily turned his face toward the sky and said, “if you don’t like my face, that’s fine. I won’t pray then. I am out here to perform your prayer, not mine.” Deen Muhammad looked at me, “Saad bhai, believe me, within two minutes the clouds and rain were gone. It was suddenly a bright sunny day! Baba Ji then ordered everyone to set up the prayer mats.”

Rizwan said, shaking his head, “Woah, such big words. If someone could just say them then he must be someone big. What big words could he utter... If anyone else had said them, it would be a grave blasphemy.”

Deen Muhammad would later explain to me why the Pir’s seemingly insolent address to God should not be viewed as blasphemy. “Certainly, if anybody else uttered it [it would be blasphemy]. But this conversation [of the Pir with God] is taking place with a beloved, with a friend. Baba Ji was a true friend of God. He wasn’t addressing a Sahib [man of status] but a friend. With a Sahib, you refer to people as muhtaram [with deference]“

“I am not in the mood for a funeral right now,” he told them in almost blasphemous fashion, “I am in the mood of chai.” I say almost blasphemous because these words would ordinarily be considered disrespectful speech against God’s will and the funeral prayer. According to Deen Muhammad, the Pir stood up, walked straight to the town center, and addressed the corpse, “oh, Fazal! Go make some tea already.” Fazal immediately woke up from death and rushed to make tea for the Pir.

“God is great!” exclaimed Rizwan in awe. “Fazal continued to serve tea to the community for many years after that,” Deen Muhammad said.

Deen Muhammad distinguished between two modes of address: address toward a friend and toward a person of status. During the latter, one must strictly conform with the formal rules of avoidance and deference that ordinarily govern one’s comportment toward a social superior. But as a friend, the Pir could speak in a more carefree, intimate, and informal manner with God. In fact, the successful performance of this joking relation with God—that is, not being charged with blasphemy— confirms the Pir’s extraordinary closeness to God. By getting friendly with God, the Pir demonstrates that he and God are close, so to speak.

12

“The spiritual comb of marriage.” This poster advertises the services of a Sufi Pir who provides an enchanted comb that could brush away deadlocks in one’s marriage.

REFLECTIONS

Stories and Everyday Archives of Truth

By Alisha Cherian

Doctoral Candidate

It was a late Friday afternoon, and I was traveling from the eastern end to the northern end of Singapore. I boarded the bus with an Indian woman who looked to be in her forties and a friend of mine, Rakesh, a Malayalee man in his thirties. There weren’t that many empty seats left, so we were all going to need to sit next to someone. The Indian aunty, who got on ahead of me, sat down next to a Chinese woman who looked to be about a decade or so older than her. The seats directly opposite them were the only ones in a pair, so my friend and I filed in next. Immediately, I noticed the Chinese aunty bristle. She clutched her bag closer to her body, shrinking herself towards the window. She rummaged through her purse and pulled out a rose-scented nasal inhaler, tucking it under her mask and audibly sniffing it every now and then. At one point, when there was still a stretch of highway to go before the interchange, the Chinese aunty stood up and made to move into the aisle. The bus swerved suddenly, and she lurched forward, knocking into Rakesh’s knees. She steadied herself on the pole, turned back, and glared at him, before going over to the section of the bus meant for wheelchair users and strollers. She stood there for about ten minutes before we came to our stop and we all alighted.

Later that evening, once we were off the bus and having dinner at a hawker center, Rakesh and I discussed what had happened. I posed several scenarios that could have potentially explained the Chinese woman’s behavior – what if she was worried about Covid? What if she had had a cold and the inhaler was an off-brand Tiger Balm? What if she had wanted to stretch her legs or was running late for her next bus and wanted to make sure she was the first to get off? Rakesh pursed his lips and looked pointedly at me while

he said sarcastically, “or, she just didn’t want to sit next to some smelly Indians.”

During my fieldwork, there was a trend on Singapore TikTok where Indian Singaporean Tokers would film themselves, with their front camera on an MRT train, their eyes smiling, some with their heads nodding proudly, tilting their phones to show that they had empty seats on either side of them. They would then switch to the phone’s rear camera to reveal all other seats in the compartment full with some folks even standing. On the screen, there was overlaid text reading some iteration of “exercising my Indian privilege” or “enjoying my Indian privilege”. The joke was that, in a crowded city like Singapore where over fifty percent of the population makes daily use of public transport, it was a rare moment of respite to have space to yourself on a train or a bus without being hemmed in on either side. However, the reason these TikTokers were able to enjoy all this space was,

13

REFLECTIONS

Photograph taken by Alisha Cherian

according to them, because Chinese and sometimes Malay Singaporeans did not want to sit next to Indian passengers who they imagined to be "dirty" and "smelly".

I spent most days of my two and a half years in Singapore on long public transport commutes to different parts of the city. I, too, started to notice a discernable pattern of who would get sat down next to and who would not. Many of my informants relayed similar experiences where they’ve either noticed being the last ones to be sat down next to, if at all, or even at times, Chinese Singaporeans standing up and moving after they sat down next to them. Whether or not there was a trend in actual statistical terms of Indian people being avoided in these public settings (I would guess yes), and whether this trend was due to specifically racially motivated reasons (ditto), was, unfortunately, beyond the scope of my research as well as most Indian Singaporeans who would vehemently argue the same. However, what was key was the ways in which many Indian Singaporeans then made sense of these encounters as well as other everyday racial phenomena that, similarly, could also not be "proven" as easily. Going up against dominant state and civil society rhetoric about a successfully racially harmonious nationstate where all four racial groups (Chinese, Malay, Indian,

and "Other") are treated equally, many Indian Singaporeans would tell me how they were often questioned and doubted by folks from the Chinese majority who believed these hegemonic narratives. They would be met with the same line of hypothetical questioning I had presented Rakesh with that evening, laughed off as “being too sensitive”, or accused of trying to “start trouble”. And so, many Indian Singaporeans would assert truth claims about their lived experiences of Singapore’s racial structure while placing these encounters into personal and communal life histories of formative interactions and encounters where racial logics were made known more explicitly.

For example, Ishan, a Tamil man in his mid-thirties, remembered how in Primary 1, when he walked past a Chinese girl on his way to the bathroom, he had accidentally brushed past her, his arm barely grazing hers. She glared at him and “wiped it off”, as if he had left a trace of himself on her. His classmates in later years would in all seriousness tell him that his skin was dirty because it was brown and that he had better use an eraser to rub off both the color and the filth it evidenced. Divya, a Malayalee woman in her late thirties, described a lifetime of being teased in school for being "smelly" and later having to admonish coworkers and friends who would crack jokes about Indian people being malodorous or ignore Chinese Singaporeans of all ages who would pinch their noses as she walked by. Aunty Reena, a Malayalee woman in her early sixties, remembered vividly how a teacher had lectured their post-war Primary 1 class on personal hygiene, pointing to the Indian girl in the class with the darkest skin, and warning that if they did not bathe regularly, they would look like her.

This repertoire of lived experience was laid out for me in semi-formal interviews as well as in casual conversations at dining tables or over a drink at a bar, many times as part of larger group conversations where the story being retold was that of a family member or a friend of a friend. All these stories collectively (re)established the known stereotype that Indians were thought of as "smelly" and "dirty", a stereotype that Indian Singaporeans believed structured much of their encounters and interactions across race in public urban space. Thus, even when people were not "telling on themselves" by pinching their noses, wiping away imagined dirt, or sometimes even explicitly saying things like “don’t sit next to that dirty one”, Indian Singaporeans drew from their personal and shared knowledge of these racial logics to understand what others might perceive as more nebulous encounters. Against a local hegemonic culture of statistics where numbers were presented as the language of truth and yet sometimes used to mask if not also perpetuate social inequality, these memories served to provide evidence of what was otherwise often disbelieved about Indian Singaporean everyday lived reality.

14

REFLECTIONS

Photograph taken by Alisha Cherian

REFLECTIONS

Beliefs and Believability During the Fieldwork in Mayfair and WashingtonGuadalupe

By Barbora Spalová

Visiting Scholar

01/02/2023, Redwood City

After weeks of uneasy family management in the new environment, I am eager to start the research. How will people from new monastic communities understand and respond to my aims? In the project, I developed some descriptive aims (the character of the counterculturality of the new monastic movement, their diagnoses of the problems of the contemporary world, and their responses), some theoretical (what the religious and non-religious mean for new monastics) and some more practical (bringing the experiences of American new monastics to the dialogue with their “spiritual relatives” in Europe). In the contact letters, I link my previous research about the renewal of monasticism in Central and Eastern Europe after communism to the project, saying that this research affected me professionally and personally and that I expect to see a somewhat similar reinterpretation of how the new and old monastics had to do with the monastic tradition.

01/08/2023, Downtown San José

The life of the Shalom Iglesia, the church started by the Servant Partners community in San José eight years ago, is slowly recovering after the Christmas break. A pastor answered my contact e-mail: “I’m quite intrigued by your work!Infact,Iamworkingonnewmonasticismtoofroma different angle — trying to start a lay movement of justice and compassion ministry. I’m in the midst of applying to a PhDprogramtostudythispursuitmissiologically.So,among alltheSPsites,Ithinkyou’veendedupattheonemostlikely tospeakthelanguageyou’retryingtotalk.” But he doesn´t show up today; he is ill with covid. Another pastor is informed I am coming and recognizes me immediately: “Bienvenido!” Before I can say something to introduce myself, he already knows: “It is good, Barbara, that you are here. It is not by

accident, HolySpirit sent you here.You know, people have alotofprejudicesaboutMexicans,thattheydrinktoomuch andhavemanywomen,butitisnottrue.Andyoucanwrite about it; you can prove it.” I feel certainly honored to be recognized as sent by the Holy Spirit. Still, at the same time, I am registering that people associate new aims with my project — academic exchange and support in emancipatory or recognition efforts of the Mexican neighborhood in San José.

01/22/2023, Downtown San José

Thursday, I could not attend the Bible study group; I was in the hospital with my teen daughter, who started to have panic attacks as soon as we arrived in the US. Today I came to worship with my baby daughter. When the pastor sees me, he calls his wife, puts my hand into hers, anoints them with a fragrance “for inviting Holy Spirit” as he says and prays: “God,youknowBarbara,youalsoknowherdaughter, you will bring her peace and you will provide Barbara with wisdom…” The prayer is long; I have Noemi on my hands and four bags hanging on me; I would like to put it all somewhere, but the pastor speaks without pauses; I find it funny. I wish I would have the faith he has, and I am trying to imagine myself believing that it really helps, that my daughter would be miraculously healed. Or that I would suddenly know how to speak to her. That peace comes to the family. It recalls the images from the Jehovah´s Witnesses magazines, which finally makes me laugh.

01/23/2023 Stanford

The next day, Khando speaks during the Brown Bag about ethnographic poetry and asks us to try it. I remember the moment from the children’s Sunday class yesterday:

15

REFLECTIONS

Elias’s hand gently touches Noemi’s.

He is only a year and a half old but already a servant.

He is going to the slums of Bangkok.

He will learn Thai quickly, for sure.

How long will he stay there?

How long will those he will serve with his trusting look stay there?

It is interesting to think about the fieldwork experiences as about the topics for a poem. Do these fieldwork “poetic moments” have something in common? Some strange indeterminacy, unnameability, tension can be felt from them. Pity that the system for evaluating scientific performance established by the Czech government would probably not accept the collection of poems as one of the results of my project.

02/16/2023 WashingtonGuadalupe neighborhood, San José

I went to Jennie´s house two hours before the Bible study; we agreed to do an interview. The Servant Partner staff rent the houses in this neighborhood and in Mayfair to fulfill their mission to build friendships with the urban poor. The neighborhood includes approximately 12,000 residents and is about 85% Latino, including many recent immigrants. The residential areas take up a little less than a square mile for a population density of approximately 15,000 per square mile. Jennie´s baby needed a little nap, so to my delight, we went for a walk. As we are passing the streets, Jennie shows me the houses of friends, but very often, she says: those are people who had to go during the covid when they lost their job, those moved to another state because of the high rents, these three families had to move to one house, you can see how many cars they have around, the father of this family disappeared so the mother could not afford it and went back to Mexico… The realization of the new monastic call for stability makes the Servant Partner staff play the role of memory holders of the neighborhood. When it comes to the discussion about the sustainability of the local public school struggling with a lack of students, the Servant Partners can witness the continuity of good work this school provides to families struggling with poverty, racism, criminality, and gang violence. The more affluent families slowly moving into the neighborhood try to convert the public school into a charter one or start a new one, but Jennie wants to send her girl when the time comes to this beloved public school. So, she started to volunteer with her little baby in the Teen Center of the school. It is her ministry just to be there and build the relationships.

When Annie started to speak about public school, I had a

question in my head but felt embarrassed to ask it. Knowing how big an issue schooling is for the child’s future in the US, is she sure about sending Lola to this endangered public school? What is the belief behind this decision? Parenting is always part of the parents´ faith, but the communal kids experience more than the faith of parents; they are parts of the countercultural community their parents choose.

Was my belief that I could manage my work with the role of the mother of five kids right? The belief that coming here would be an important, maybe not only positive, but important experience for everybody? Or is this my belief that what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger, behind my daughter’s breakdown?

04/24/2023 Green Library

The time is becoming short, and I try to organize the dozens of interviews and hundreds of pages of field notes to see what I missed. There are some topics that I don´t dare to go into: racism or the character of the secularity of American society don’t seem graspable for me now. I wonder what would bring the re-reading of my material about the practice of monastic stability through the lens of migration and urban studies. I care about being in contact with the missiology aims of the Servant Partners’ pastor but also to bring him and other people of a similar audience a fresh perspective. But I would like also to approach the puzzle of counterculturality of the new monastics. To honor the stories of my friends whose parents or grandparents don’t agree with their ministries, their lives in poor neighborhoods, their abolitionism. To make sense of the stories hard to believe for me of people being shot by police using rubber bullets during the George Floyd protests. To seek the reconciliation together with another friend whose grandma wrote her a letter to make her aware that she lives in sin doing this ministry. The effort to fulfill these aims will surely bring to light some of my beliefs. And maybe I could hope for reconciliation also in my family.

16

Photograph taken by Barbora Spalová

Studying the PostImperial in Post-Disaster Turkey

By Miray Cakiroglu

Doctoral Candidate

Repetitions

All things that come to the foreground begin to make sense in terms of comparisons. In 2023 Turkey, a theme of repetition is prevalent. The ruling party declared its campaign slogan for the upcoming elections– “Turkey’s Century.” This is in reference to the centennial of the Turkish Republic and, at the same time, an invitation to view the elections through the lens of the closure of an era and the beginning of another. In anticipation of directions to take, comparisons arise between experiences that come into view as turning points in retrospect. Yet, comparisons also arise even when they are not desirable.

I entered a bomb explosion scene in Taksim when I arrived from school at the field in Istanbul. A news ban and internet slowdown soon followed. The wi-fi network at the hotel did not allow me to connect to the VPN, so I could not access my Twitter feed. I could watch the mainstream news channels on TV, which circulated images of a female refugee accused of the incident where six lives were lost. As we were approaching the elections, many asked whether this incident was the harbinger of a bloody episode that could resemble the aftermath of the 2015 elections. The explosion in Taksim on 19 March had marked a period of events that culminated in repeat elections in 2016. One hour into the field, I was also wondering, as did others, whether we could expect more in the coming days.

The explosion had only made the headlines for a short time. A couple of months into fieldwork, an earthquake of immense intensity hit Turkey. Suddenly, back in the present time of another devastating catastrophe, the horizon was not the expectation of violence nearing the elections but that of the aftermath of 1999. The “Big Southeast Earthquake” of February 2023 has been compared to the 1999 Izmit earthquake. Those who have memories of 1999, besides feelings of personal loss, have also drawn links between drastic turns in the country, including the 2022

elections that brought Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP) victory in the wake of the disaster. People mostly attribute the blossoming of a robust civil society in Turkey to that earthquake: When they lifted their heads from the rubble, they saw not state agencies that rushed to relief but each other. The air in Istanbul thickened with grief upon news from the southeast and worries of the “expected Istanbul earthquake,” as it is commonly called since 1999.

Figures circulate. A prominent former journalist, a figure from the past, is now running as an MP in the elections. The journalist interviewing him jokingly asks whether he could open the parliament the day after the election as the most senior parliamentarian. He is one of the figures associated with an era and seems out of place, having outlived that period. He had played an active role in the “peace process” as a journalist who studied the circumstances of reconciliation with the armed wing of the Kurdish movement closely and published reports for steps to take. After a self-imposed exile in Europe, he has recently returned to Turkey, accepting the pro-Kurdish YSP’s offer to run as a candidate. The hope is that his presence will aid in passing on valuable know-how in a potential post-AKP reconstruction. He says he has found time to read much history in his self-imposed exile in the interview. Having done so, he confidently suggests that Turkey today most resembles 1908, right before the constitutional monarchy.

“May 14 is like the proclamation of the second constitution. The sultan is the same; Abdulhamid remains there. He is the one to give it anyway. Give what? Give back the constitution he canceled in 1876. Yes, the regime did change. Some throw his fez, some his hat, some his serpuş in the air… There is an emotional state in the society resembling the second constitution: “Oh, a new era is beginning!” 1

There, Not There

I came to the “field” to study Istanbul’s Rum (GreekOrthodox) community. Rum is a religion-based category defined through its subjection to the Greek-Orthodox church. In the nineteenth century, this religious community acquired a national meaning, with Greece becoming

17

REFLECTIONS

the first nation-state to emerge from the Ottoman Empire.2 Istanbul’s Rum community also connects itself to the Eastern Roman Empire. What is the present for a community that is invoked with its past? I aimed to explore it through the modes of presence and absence in contemporary Istanbul.

The Rum in Istanbul are more open about their ethnic and religious identity than anywhere else. Still, I expect to have difficulty accessing this close-knit minority. I get introduced to the former president of non-Muslim foundations in a gathering hosted to “make space” to grieve on the 40th day of the earthquake. “Don’t,” he says to me, “there is nothing to be studied.” As a response to me, looking to hear more, he adds: “I believe you want to do serious work,” taking his cue from the friend who introduces me, “You will not be able to find anyone that will give you a substantial account.”

On another day, I am trying to schedule a meeting with a prominent archivist. Non-Muslim property transfer is relegated to historians, I say; I want to discover what is happening today. I would like to see if he could direct me to people or documents. “Documents?” he responds, “there are no documents; it is only hearsay.” Later I try to take this cryptical response apart. Perhaps the archivist alluded to methods of oral history. It would not be a coincidence for him to say that. The plethora of research on population exchange primarily relies on oral history accounts. The statement to me was a surface response, the first thing you offer upon a question. Perhaps the way I start laying out the question has been wrong, and it does not immediately hit a nerve.

Yet allusions to the imperial past in connection to dispossession keep coming up in unexpected places. A journalist speaking at an event on Antakya’s future after the earthquake describes a wide frame where he thinks the reconstruction of Antakya fits.3 He says the audience is probably familiar with Armenian and Rum property. Remembering that construction has moved hand in hand with expropriation throughout Turkey’s history highlights the necessity of closely monitoring the rebuilding of Antakya, 90 percent reduced to rubble in the earthquake’s aftermath. We see that historically spatial organization corresponded to processes of identity building. Antakya was the region where borders changed the most following the bylaw of 2012 on the transformation of disaster-prone urban areas.

An anthropologist starts laying out how she became interested in rural land enclosures. 4 She became interested in a news piece covering a rural struggle against a private company buying and fencing the land in a village in western Turkey. She was particularly interested in the temporal references the peasants made back to the 1960s, a period of land occupations entwined with socialist student movements, and further back, deriving their share in land from use since ‘antiquity.’ She suggests that the 1920s was the primary accumulation of the first phase of the

drawing up of borders; the 1960s was the second phase. The rural struggles today can be understood in terms of the possibilities opened or not opened in these times.

Countdown

At the time of my writing this piece, there is one week left until the elections. I have been living since January in the Yesilkoy neighborhood, where there is a resident Rum community. It is possible to find the Ayastefanos church with decent participation any Sunday and hear Greek on a stroll along the shore. I have been primarily involved with a group called Nehna (which means “us” in Arabic). Nehna started as a website, an outcome of the collaboration of young Arab-Orthodox people from or with links to Antakya.5 It immediately took on a role of a civil initiative since the February earthquake, with the network they had in place.

Through them, I have witnessed the Rum spaces of Istanbul open for relief efforts for the non-Muslim population in Antakya and the wider community. Last Saturday, there was a charity bazaar at the Panayia Greek Orthodox Church in Beyoğlu. And on Sunday, a piano recital took place at the Zografeion, one of the two high schools still active today, to benefit students impacted by the earthquake.

On my way to the subway for Sunday’s recital, I could see

18

REFLECTIONS

One hour into the field. Taksim, Istanbul. 14 November 2022.

REFLECTIONS

cars waving flags and shouting chants down the Istasyon Caddesi. It is the crowd Recep Tayyip Erdoğan held its Istanbul meeting at the no-longer-functional Atatűrk Airport located in the Yeşilkőy neighborhood. I catch a glimpse of Erdoğan’s speech on my return from the recital.

It seemed apparent to many that the devastating earthquake drew the final line to the question marks as to whether the opposition will win the elections against the ruling party. The chain reaction of negligence that resulted in the catastrophic scale of the disaster pointed to illprepared disaster response and corruption in supervision mechanisms at all levels. In the first few days, there was no official declaration. The opposition mobilized the three metropolitan municipalities, declaring they could not wait for a 'go' from the state to act. It was common to hear the following statement: “The state is buried under the rubble of this earthquake.” This became a shorthand for many after excitedly reporting on the immensity of the experience to come to a point where they struggled to find more words.

Three months seem like a short time for a disaster of such scale to be put on the back burner. However, the prime minister invites the audience to look at the works and services they will offer in the next term. One of them is to leave no city vulnerable to earthquakes and make cities resilient to disasters. Even if we leave aside the recent experience for a moment, the promise is ringing the alarm bells for those who have lived through disasterled urban transformation, gentrification, and population displacement cycles in the past decade.

In Closing

Staying on track in what feels like a whirlwind of events is challenging. It is interesting to study something that could have been left undone from the transitional period from the empire to the republic. To focus one’s gaze on institutions founded for the social well-being of non-Muslim Ottomans, redefined in Republican Turkey, while time seems to flow incredibly fast.

One of the ways I had started imagining the time scope of my field was with an early formulation of helalleşme (making amends) offered by the opposition as a new political direction. What ‘making amends’ entails is not yet clear, nor how far back those who suggest and those who interpret are willing to extend it. In the video, when the Kılıçdaroğlu first used it, he did so vaguely:

“Our country is one of wounded people. Different groups carry different wounds. Our wounds are so deep that our souls are in agony. We are so deeply hurt that we cannot look into the future; we are stuck in the past.” 6

Whatever the result of the elections, the discussion will go from here.

References

1. Cengiz Çandar. “Cengiz Çandar Talks to Ruşen Çakır.” 13 April 2023. Medyascope. https://medyascope.tv/2023/04/13/cengiz-candarrusen-cakira-konustu-milletvekili-adayligima-gelen-tepkiler-elestiriboyutlarini-asti-bu-organize-ve-operasyonel-bir-hareket/

2. Benlisoy, Foti and Stefo Benlisoy. 2001. “Millet-i Rum’dan Helen Ulusuna (1856-1922).” Modern Türkiye’de Siyasi Düşünce Cilt 4. Murat Gültekingil and Tanıl Bora (Ed.) İletişim.

3. Bahadır Özgür speaking at “Antakya’nın Felaketi ve Geleceği” (The Disaster and the Future of Antakya”) (2023). İstos. https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=ARSGVm7u6ac

4. Begüm Özden Fırat. “Toprak İşleyenin, Su Kullananın!: 1960-80 Arası Toprak İşgal Hareketi” (Land belongs to who works it, water belongs to who uses it!: Land Occupation Movement between 1960-80.)" Talk at TÜSTAV, İstanbul. 5 May 2023.

5. www.nehna.org

6. Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu. [Twitter post]. 13 November 2021. https://twitter. com/kilicdarogluk/status/1459455266831937536/

19

A Conversation with Jean-Thomas Martelli

scholarship draws from adjacent fields of knowledge, in particular political anthropology. My exposure to interdisciplinarity in a range of area studies departments—King’s India Institute, Center for International Studies (CERI), Centre de Sciences Humaines (CSH)—made me receptive to a wider range of interpretive scholarship on South Asian politics, irrespective of its formal disciplinary moorings.

Visiting Scholar

Could you tell me a little bit about your current work and what inspires your current research?

My work is inspired by the following question: how do some people get to speak for others in autocratizing democracies?

I believe this question is important because modalities of representation, such as expressions of proximity to the masses can damage democracy rather than strengthen it. All in all, the main concern of my work is to identify, catalogue and interpret the various ways in which democratic representation is performed in contemporary India. As part of this, I research populist discourses, youth activism, generational politics, political professionalization and practices of the self.

In the past few years, I developed a strong expertise in combining ethnographic and computational approaches. I aspire to build on this experience to research everyday political labor such as political advisory, speech-making, digital outreach, campaigning and political brokerage. In addition to ‘playing’ with advanced methods of text analysis, data mining and natural language processing, I specialize in corpus design, extraction, and compilation.

What role has Anthropology played in your research?

Although my training is grounded in political ethnography, my

I learned from anthropology a taste for enlarging the scope of politics beyond the study of formal mechanisms of political representation such as elections. I also use the anthropological canon to nuance positivist hypothetico-deductive approaches in American political science, in particular through grounding political theory on deductive field-centric evidence. Third, the way I look at politics is tinted by classical anthropological quarrels, in particular the one concerned with equality and hierarchy in South Asia, from Louis Dumont to M.N. Srinivas, including contemporaries such as Mukulika Banerjee, Anastasia Piliavsky and Alpa Shah. From this, I conceive anthropology as a liminal space for experimentation that very much informs my conceptual work on political representation.

Think about the topic of belief, credibility, and truthfulness. How does this topic play a part in your work?

I must admit that I have not much engaged with the topic of belief, credibility and truthfulness in my own academic work, although I am currently coordinating a special issue on digital politics in India, which touches on questions of fake news and disinformation at the interface of online and offline spaces. Questions of trust are often nested within considerations of political communication and electoral success. For instance, Neelanjan Sircar has recently introduced the term viswas (trust, assurance or faith in Hindi) to understand the personal and non-institutional ‘connect’ that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi established with his voter base. I follow academic debates around these lines very closely. I also have personal interest in understanding how bahubalis, strong men with criminal records, are building political patronage on boss-like notions of force that rely paradoxically on trustworthiness and paralegal credibility. A subtype of bahubalis —conmen—fascinates me even more. I read media stories on high-level Indian political and business scammers—Sanjay Sherpuria, Kiran Patel, Tihar-jailed Sukesh or a mysterious yogi allegedly pulling strings at the Indian National Stock Exchange (NSE). This does not yet constitute a topic of academic scrutiny, but in the future…who knows!

20

INTERVIEWS

A Conversation with Tatjana Thelen

Could you tell me about your educational background?

When answering this question, I’m tempted to smooth out a pathway that wasn’t straightforward and didn’t feel that way either. I started my studies rather late and unambitiously, making my later career unlikely. However, those years certainly contributed significantly to my academic personality and research interest. When I finally studied anthropology in Cologne, Thomas Schweizer became my supervisor. He focused on social networks and had close research connections with UC Irvine. Thus, my first fieldwork experience was in a collaborative project only 400 miles south of here.

My PhD at the Free University in Berlin was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation within an interdisciplinary program called “Comparison of Societies”. I was interested in what was happening after the demise of socialism and undertook fieldwork on privatization in Romania and Hungary. My supervisor was Georg Elwert, an expert in West Africa with a focus on conflict theory who inspired my perspective on the role of arbitrary violence in social reproduction.

After defending my thesis, I joined the Legal Pluralism group headed by Keebet and Franz von Benda-Beckmann at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle/Saale. My work on the state and social security profited deeply from their insights into the working of law. Besides them, Richard Rottenburg at the University of Halle-Wittenberg and his STS network, LOST, exerted the greatest intellectual influence. After I had already left Halle for the University of Zurich, he and Keebet sponsored my habilitation based on my research at a former large enterprise in eastern Germany.